KADS 2018

22 April-3 June 2018

When the notion of time disappears

3 June finissage 15:00 – 19:00

Programme

15:00 Ongoing performance: Nina Glockner at EINDPUNT, Havenstraat opposite # 1

15:30 Welcome

16:30 Tour along the art works of KadS[Kunst aan de Schinkel] 2018

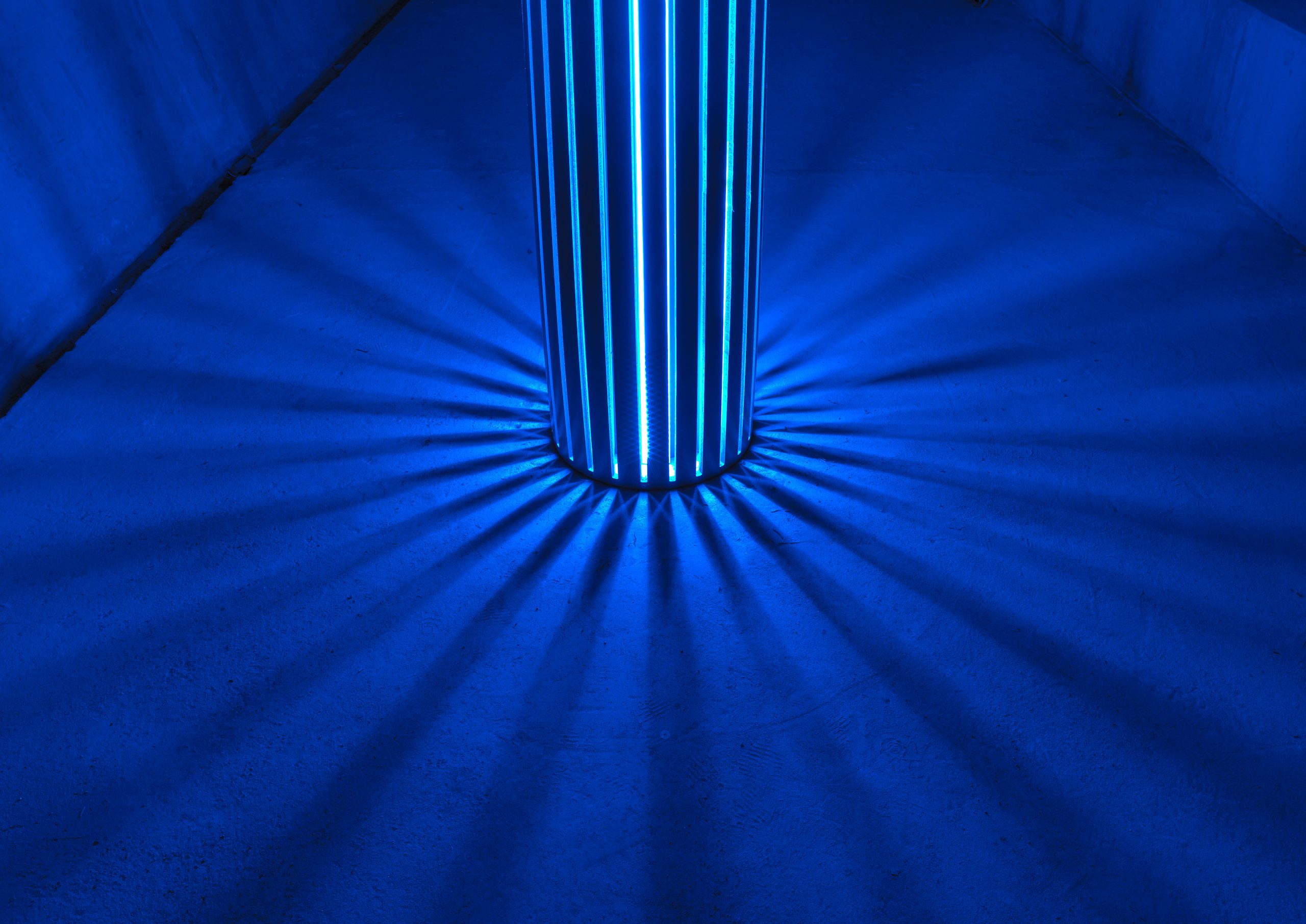

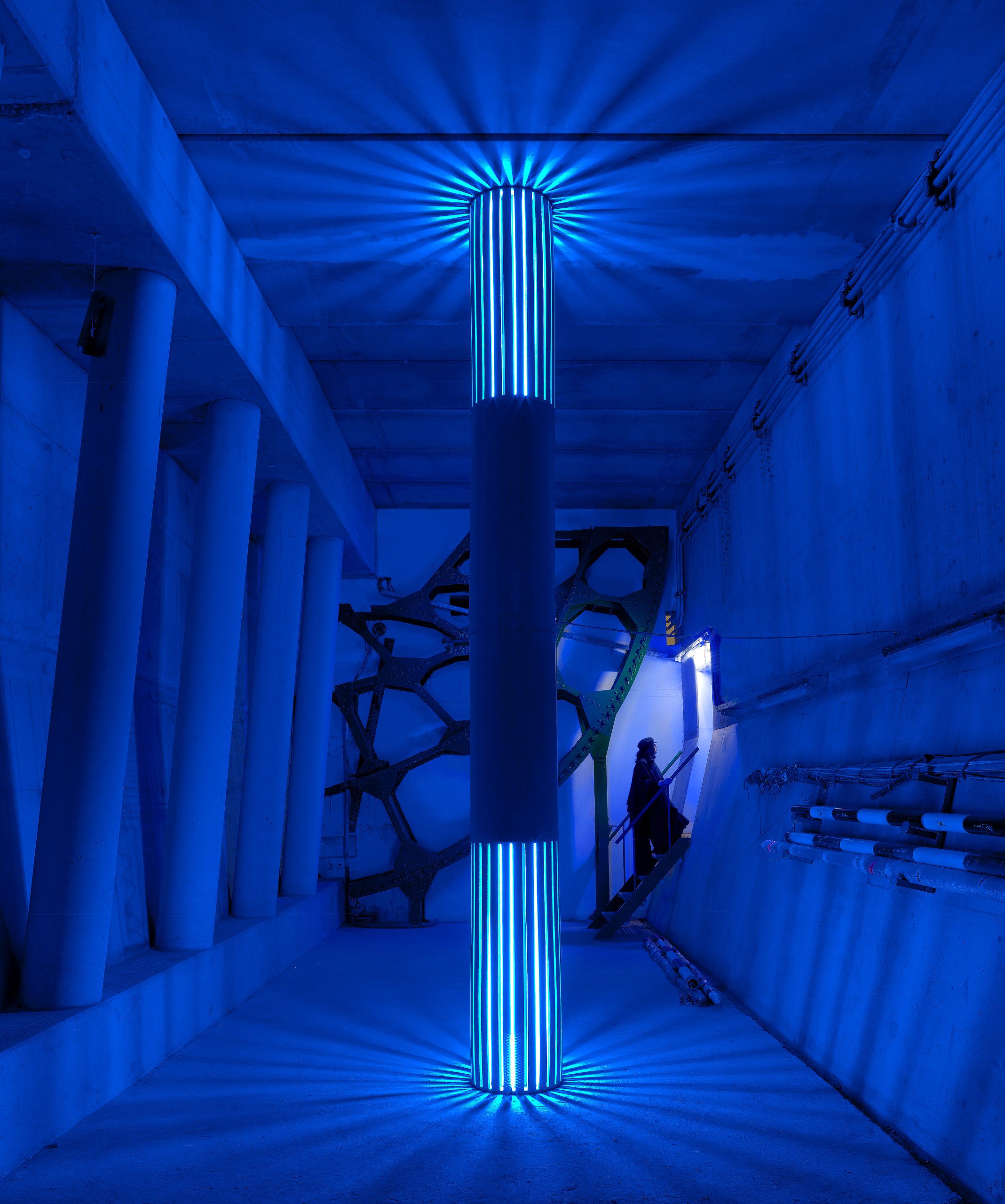

18:00 Visit the Zeilbrug basement with the light installation of Tamar Frank

17:30-19:00 Jazz music by Elsemieke van Aalst (vocals) and Jessica van de Brug (guitar) + drinks

27 May at 15:00 hrs lecture and debate moderated by Cees de Boer with Gerrit Hoogsrtaaten

20 May at 15:00 hrs photography workshop by artist Popel Coumou. The participants will be making a collage, inspired by the working methods of the artist

22 April at 3pm Opening

Admission to the KadS art route and activities is free!

Sign up for a guided tour along the locations: artfoundation@soledad.nl

Opening times

thu-sun 11:00-18:00

The locations Zeilburg cellar and Huis te Vraag have their own opening times

Closed on 27 April 2018, King’s Day

Information centre KadS

Sloterkade 171 Amsterdam

T +206151395

thu-sun 11:00-18:00

WHEN THE NOTION OF TIME DISAPPEARS

MARISOL FERRADASOur lives are controlled by the notion of time from the very beginning: childhood, the time to start attending university or get a job, the time to make a career, find a partner, have children, get old and the time to die. What happens when this notion of time disappears? Where do we find ourselves then? Do we enter a different dimension? What is the past and what the future? Or do they melt together into another entity of time?

For KadS [Art at the Schinkel] 2018, some ten artists have been invited to investigate the Schinkel neighbourhood, reflect and act upon the question: What happens when the notion of time disappears? How do we achieve a state of timelessness? Through meditation? Can an artist make time stand still or suggest that it does? Or do we achieve timelessness via the laws of physics and the associated ideas and fantasies about time travel, now or in the future?

Our notion of time is static, but the theory of general relativity has taught us that space-time is variable. Stronger gravitation makes time go slower. Time probably doesn’t even exist at the edges of a black hole where gravity is so extreme nothing can escape from it. Should we move to a black hole to be able to let go of time? We find ourselves in a certain period of time; are we ‘caught’ in this time? In the future, will we move on to places where time is different?

There are several spots in the Schinkel area where time seems to – almost – disappear. The old cemetery Huis te Vraag, for example. But also the river Schinkel itself and even the sky over it are phenomena which are less tangible and more fleeting, they introduce a kind of timelessness in this part of the city.

It is likely that the elderly in the neighbourhood experience time quite differently than young people. How do they experience the course of time in their daily life? Do they feel they have more time or maybe less? Does time pass quickly or very slowly?

The artists involved in the project investigate the notion of time, throwing light on the contradictions of timelessness. They might even be able to make time stand still or disappear, albeit for a very brief moment.

‘Time is a game played beautifully by children.’

Heraclitus

HOW TO STOP TIME

SANNE DE VRIESPeople often say: I wish I could make time stand still. If it were up to us, we’d stop it ticking away for good – so we would no longer feel its pressure. This very idea suggests that time is always moving: flowing; walking, running. Because we can feel it passing. But of course, time isn’t the one moving – we are. Our concept and sense of time are inextricably bound up with the finite nature of our lives. Our limited time on Earth creates a point on the horizon. We use it to gauge our distance: a distance that is steadily shortening. And although human life expectancy continues to increase and people say the first human being who will live to a thousand has already been born, for the time being, that end point on our horizon isn’t going anywhere. This makes it rather difficult to make time stand still – or disappear altogether. What we can do is change our ideation of time. If we adjust our concept, we can deal with time in a different way and vice versa will time affect us in a different way by its – always-too-swift – passage.

People around the world conceive time in a variety of ways. In the Western, linear concept of time, our future lies before us – like a long road that we’re doggedly walking along. Behind us lies the past – the road already travelled. We keep looking forward, toward that point on the horizon where our road will, inevitably, one day end. Many Eastern cultures have a cyclical concept of time, in which time moves in circles that will eventually turn back to a previous point – over the course of one or more lives. The Malagasy of Madagascar see time as something that moves through you rather than as a road that lies before you. Time passes through our heads, from the back to the front. According to the Malagasy, our future lies behind us, where we don’t have eyes – which is why we can’t look into it. Time moves from the future into our head and mind, into the present, where we become aware of it. And time once again leaves our heads through our eyes, and is cast before us into the landscape of the past, which we can look out over and learn from.

As a result, the Malagasy concept of time is more fluid than the Western ideation commonly encountered in the Netherlands. The future is something that lies behind you: you feel less pressure to anticipate it through your actions, since you have no hope of influencing it anyway. Whatever happens, happens. Nor do the Malagasy feel the same need to memorise the past – by taking pictures, for example. Whatever happened, stays. It’s a more peaceful state of mind, since the past becomes something you can survey, from where your ancestors watch over you. And as a result, the Malagasy have a different relationship with time itself too. While we start running when we see the bus is about to leave its stop – even though the next one will be here in 5 minutes’ time – the buses in Madagascar don’t have timetables: they leave when they’re full. And while we’re so pressed for time it often takes a month before we can meet up with a friend, when the Malagasy run into a friend, they spend the rest of the day together.

You could say our ideation of time, our mental image of it, is like a space that always surrounds and moves along with us. And we often experience this space as a permanent fixture: it feels as if we have no power over our idea or sensation of time. However, other cultures and time concepts can show us that this space can also look markedly different. In 1984, Foucault introduced a new concept, in which space and time are interrelated: heterotopia. Its literal translation is ‘other place’. A heterotopia is a place or space that works different to other spaces – it seems to form an alternate world within the world. Foucault names a number of examples, including cemeteries, prisons and museums. These spaces are distinguished by a variety of qualities, one of which is their effect on time. The heterotopia changes time and changes its atmosphere, so that its behaviour is different to what we encounter in most spaces. Time is linked to the past – in a cemetery, for example – or seems to be frozen – like you see in prisons.

The museum – and with it, this exhibition – can also be seen as a heterotopia where time never stops rising and descending. Time has no permanent location, no fixed pace. It is an environment that incorporates a full spectrum of times, and as such seems to seek a state of eternity – or even exist out of time altogether. And if you were to see the museum or the exhibition as the home of art, you could actually say that the works themselves – including the works in this exhibition – are heterotopias in their own right. By engaging with the world via different paths, a work of art can open up a different perspective on time that goes beyond the point where words are sufficient. Art can enable us to think in new ways because it is not limited by preconceived frameworks – including the one of time. It doesn’t try to tie time down, describe or categorise it. Rather it approaches and approximates time, without judgement or a fixed form. Therefore it is able to mould time, slow it down or travel through it. And through art, we can get to know time as we truly experience it: changeable and unpredictable.

Sanne de Vries

artistic researcher & writer

www.sannedevries.net

DE TIJD BIJ DE START

CEES DE BOERDeze aflevering van Kunst aan de Schinkel gaat niet over de tijd. Althans niet over de tijd waarnaar wij vragen als wij vragen ‘Wat ís de tijd?’ Dergelijke wat-is? vragen brengen ons altijd in verlegenheid.

Augustinus, de kerkvader uit de 4e eeuw concludeerde als een van de eerste denkers: ‘Wat is de tijd? Wanneer maar niemand het aan mij vraagt, weet ik het; wil ik het echter uitleggen aan iemand die het mij vraagt, dan weet ik het niet.’

Augustinus wist zich uit zijn dilemma te redden, door de tijd aan de heilsgeschiedenis van de bijbel te koppelen en deze geschiedenis op zijn beurt met de menselijke ziel te verbinden. Verleden, heden en toekomst worden bij hem aspecten van één tijd, namelijk de tijd van het Christendom die een heilsgeschiedenis is en die altijd de waarheid spreekt: ‘Er is een tegenwoordige tijd van het verleden, een tegenwoordige tijd van het tegenwoordige en een tegenwoordige tijd van het toekomstige.’ Deze drie tijden komen overeen met de drie vermogens van de ziel: het verleden staat voor de herinnering, het heden voor de aanschouwing en de toekomst voor de verwachting.

Het model van Augustinus heeft gote invloed gehad. Maar vanuit het heden bezien, herkennen wij vooral de constructies die vanuit dit model mogelijk werden: de constructie van een historisch verleden, de constructie van een identiteit in het nu, en de constructie van een toekomst, en bovenal de gelijktijdige constructie van deze drie tot een omvattend antwoord op de wat-is? vraag.

De Nederlandse filosofe en essayiste Joke Hermsen heeft de afgelopen jaren studie gemaakt van het fenomeen tijd. Zij vestigde bijvoorbeeld de aandacht op wat in de Oudheid heette het Kairos-moment, dat niet zozeer een moment in de tijd is, alswel een situatie waarin een eenheid van denken, handelen en menselijkheid tot stand komt en waarin iemand de gelegenheid die zich voordoet begrijpt en met zijn hele wezen daarnaar handelt. Het moment van begrijpen en het moment van grijpen vallen samen en bepalen zo een eigen tijd/ruimte.

Hermsen besteedt aandacht aan de filosoof Ernst Bloch, die met zijn onderzoek van het principe van de hoop op de toekomst gericht is. Hermsen besteedt aandacht aan de filosoof Hannah Arendt, die juist veel aandacht besteedt aan de vraag waarom mensen steeds weer beginnen met dingen te doen, steeds weer het initiatief nemen om zaken te veranderen, hoewel zij daar objectief gezien misschien geen aanleiding toe hebben, integendeel – vaak wordt een nieuw begin gemaakt met de moed der wanhoop.

Om meer te weten te komen over hoe wij omgaan met abstracties als ‘ruimte’ en ‘tijd’ – die toch zo fysiek onze wereld bepalen – wordt vandaag ook naar andere culturen gekeken en naar hoe daar met tijd wordt omgegaan. Sanne de Vries verwijst in de catalogus van deze tentoonstelling bijvoorbeeld naar de oorspronkelijke inwoners van Madagaskar, die de toekomst opvatten als iets dat achter je ligt en dat zich door jou heen beweegt. Als ik het goed begrijp: alsof je in de trein in een stoel zit die achteruit beweegt, zodat je naast en voor je ziet opdoemen waar je naar toe gaat.

In de beeldende kunst, zoals in alle kunsten, wordt geprobeerd om de paradoxen waarin wij verwikkeld zijn, om de zinloze tautologieën die ons bevangen, bij de staart te grijpen. Wat gebeurt er óók, buiten de meetinstrumenten van de klok en de centimeter? Wat mij betreft is het primaire doel van de kunst om de ogen, de oren en alles wat van onze zintuigen uitgaat – het geheugen, het nu, het beginnen, het verlangen, dat wat opdoemt – open tegemoet te treden.

Ik hoop dat u de kunstwerken van deze aflevering van Kunst aan de Schinkel zult ervaren als een inbreuk op de gestandaardiseerde ruimte/tijd die ons functioneren in zo hoge mate determineert. Ongeveer zoals het kunstwerk van deze prachtige voorjaarsdag, vandaag, die als een inbreuk en een aanvulling op onze wijk háár antwoord geeft op de vraag wat er gebeurt als de notie van de tijd verdwijnt.

DE TIJD BIJ DE START II

CEES DE BOERIn mijn openingswoord voor deze tentoonstelling refereerde ik naar Augustinus, de kerkvader uit de 4e eeuw. Hij sprak zich als een van de eerste denkers uit over de tijd op een manier die wij nog steeds als actueel herkennen:

Wat is de tijd? Wanneer maar niemand het aan mij vraagt, weet ik het; wil ik het echter uitleggen aan iemand die het mij vraagt, dan weet ik het niet.

De paradox die hij onder woorden brengt, ervaren wij nog steeds wanneeer wij ons met het thema tijd bezighouden. Augustinus wist zich uit zijn mysterieuze dilemma te redden, door het karakter van de tijd te interpreteren volgens het model van de heilsgeschiedenis van de Bijbel. Die geschiedenis was immers een van God gegeven waarheid, die ook op andere onderdelen van de Schepping van toepassing moest zijn. Deze ware geschiedenis determineerde met andere woorden de geleding van de tijd (en in hoge mate Augustinus’ visie op wat geschiedenis in het algemeen is): het Oude Testament van de Joden is het verleden, het Nieuwe Testament van de Christus is het heden, de belofte van de Verlossing is de toekomst.

Augustinus redeneert verder: als deze driedeling de waarheid is (hij is immers ook in overeenstemming met de leer van de Drieëenheid in God), dan moet ook de menselijke ervaring van de Schepping deze driedeling als basisstructuur in zich hebben:

Er is een tegenwoordige tijd van het verleden, een tegenwoordige tijd van het tegenwoordige en een tegenwoordige tijd van het toekomstige.

Deze drie tijden komen overeen met de drie vermogens van de ziel: het verleden staat voor de herinnering, het heden voor de aanschouwing en de toekomst voor de verwachting.

Het model van Augustinus heeft grote invloed gehad. Vanuit Christelijk oogpunt is het verleden overwonnen – dit leidde tot zowel de afwijzing van het Jodendom met zijn totaal andere beleving van tijd en geschiedenis, als ook de vergeving van de zonden uit het verleden in de biecht of in de schuldbelijdenis. Vanuit Christelijk oogpunt is het nu een voortdurend heilzaam heden, waarin weliswaar tussen goed en kwaad gekozen moet worden, maar waarin ook Christus voortdurend aanwezig is in de Eucharistie en in de Gemeenschap van Zijn Kerk. En er is de beloftevolle toekomst waarin een Goddelijk Heil onthuld wordt dat eeuwig is.

Zonder ook maar een poging te doen om een subtiele brug tussen heden en verleden te slaan, wil ik deze visie direct naar het actuele heden overzetten. Enigzins chargerend, stel ik vast dat we deze driedeling ook kunnen herkennen in het consumentisme dat onze huidige samenleving zo diepgaand structureert. Ik wijs op de persoonlijke én algemene verbetering van het verleden, die in elk nieuw model iPhone vervat ligt. Ik wijs op het heil van het consumeren dat altijd beschikbaar is en dat altijd op het nu ingaat, een nu zonder al te lastige bijgedachten. En natuurlijk de behoeftebevrediging die niet in het heden maar in de toekomst ligt en waar wij allen voor werken en naartoe leven – eindelijk een leven zonder complicaties, eindelijk het zwitserleven gevoel. (Zoals bekend is Zwitserland een land waar nooit iets gebeurt, of het gebeurt 50 jaar later dan elders.)

Let eens op deze structurele aspecten als u naar reclamespotjes kijkt: het verleden is er om verbeterd te worden; in het nu dienen wij een identiteit te creëren; ergens in de toekomst ligt de vervulling van ons bestaan op ons te wachten. Dit hele schema is een drogbeeld. Maar er daadwerkelijk afstand van nemen, is lastig.

Gelukkig zijn er kunstenaars, dichters en filosofen die het ons met opzet lastig maken. Zij praten tegen de meningen en interpretaties die, letterlijk, vanzelf spreken, in. Zij tonen de dingen op een heel persoonlijke manier, zodat een algemene visie voor een moment op de achtergrond raakt en er ruimte komt voor degene die naar het kunstwerk kijkt en het ervaart. We mogen van kunst (in al haar vormen) verwachten, dat de ruimte/tijd even zijn clichés voor zich houdt en dat we de ruimte/tijd krijgen om ongewenste, onverwachte en soms ronduit zinloze antwoorden te geven op de politiek correcte vragen. (Oscar Wilde: All art is quite useless.)

We hebben de kunst hard nodig, tegenwoordig, als contrast met het consumentisme dat – ook in de kunstwereld – zo alles overheersend is geworden. Kunst geeft tegenwicht tegen de definitie van de mens als het dier dat dingen doet met dingen.

Ik heb aangestipt dat het thema tijd in de kunst, ons confronteert met de constructies die wij creëren om de tijd aan ons begrijpen te onderwerpen. Dat het hierbij over sociale, culturele constructies gaat, maakt de socioloog Norbert Elias (1897-1990) duidelijk in zijn belangrijke Een essay over tijd uit 1975. Ook een recente studie over tijd, van de hand van de gezaghebbende natuurwetenschapper Carlo Rovelli (1956) The Order of Time (2017), maakt duidelijk dat de fenomenen ruimte en tijd niet zijn terug te vinden daar, waar de wetenschapper de fundamentele bouwstenen van de kosmos observeert. Rovelli concludeert voorzichtig dat de categorieën ruimte en tijd meer met het perspectief van de onderzoekende mens te maken hebben dan tot nu toe gedacht.

Des te belangrijker is, denk ik dan, hoe wij naar ruimte en tijd kijken en hoe wij ons bewust kunnen worden dat het geen objectieve, meetbare gegevens zijn. Juist hier speelt de kunst een belangrijke rol – een belangrijke strategie van de kunstenaar is immers het de-construeren van wat vanzelf spreekt: analyseren, ontrafelen, vervreemden en verschuiven van de werkelijkheid waarin wij (denken te) leven.

In meer specifieke zin is de-constructie het tegen elkaar uitspelen van betekenissen die tot een zelfde veld – ‘ruimte’ ‘tijd’, ‘sekse’, ‘status’, etc. – behoren. Als voorbeelden citeer ik enkele werken uit de moderne kunst – met dank aan Sanne de Vries, die op de website MisterMotley een serie artikelen aan kunst en tijd wijdde. Afbeeldingen van de genoemde en ook andere kunstwerken kunnen worden bekeken via de bijgevoegde links.

Joseph Kosuth (USA, 1945), Clock (One and Five), 1965

www.mistermotley.nl/art-everyday-life/de-kunst-en-de-klok

Naast elkaar zijn opgehangen: een foto op ware grootte van een klok, dezelfde klok die de tijd aanwijst van de lokatie waar het werk zich bevindt, en drie uitvergrote lemmata uit een Engels-Latijn woordenboek: time, machination/machine/machinery en object.

Een werk als dit maakt ons bewust dat ‘tijd’ niet een ding is maar een veld van betekenissen, objecten, afbeeldingen, definities, machines. De afbeelding van een klok naast een werkende klok maakt duidelijk dat tijd een machine is; de definitie van het woord machine in combinatie met het geassociëerde woord machinatie, maakt duidelijk dat het een kunstmatige én een bedrieglijke machine is. Kosuth deconstrueert ‘tijd’ met behulp van wat wij over ‘tijd’ weten. Het resultaat is een herordening van informatie, misschien ook nieuwe informatie over wat ‘tijd’ is.

Simon Phillipson (UK), On the Origin of Species. Charles Darwin. Evolutionary Edition, 2014

www.mistermotley.nl/art-everyday-life/na-verloop-van-tijd

Phillipsons uitgave van het in de 19e eeuw revolutionaire en schokkende boek van Darwin is niet zozeer een wetenschappelijke editie, als wel een kunstenaarsboek. Phillipsons ontrafeling raakt aan de sfeer van de wetenschap op een filologische manier: op de rechterpagina lezen we de tekst van de zesde editie van 1872 van de hand van Darwin zelf, op de linkerpagina lezen we alle veranderingen die de auteur heeft doorgevoerd sinds de eerste editie van 1859. Dit boek laat de evolutie van het boek van Darwin zien en daarmee de evolutie van zijn denken.

Phillipson deconstrueert het idee dat wat in een boek, in een wetenschappelijke studie staat, de waarheid is. Hij wijst op de sporen van de evolutie van Darwin’s waarheid en presenteert deze zonder ze te interpreteren. Hij maakt daarmee o.a. inzichtelijk dat de laatste editie van Darwin niet het laatste woord over de evolutie betekent, maar een moment binnen het nadenken over de evolutie van het leven op aarde. Phillipson maakt tevens duidelijk dat ‘voortschrijdend inzicht’ zijn eigen waarde en schoonheid heeft en, in tegenstelling tot wat deze frase tegenwoordig in de politiek betekent, niet een doekje voor het bloeden is en dus onbetrouwbaar.

On Kawara (Japan 1932 – USA 2014), Today (januari 1966 – januari 2013)

www.mistermotley.nl/art-everyday-life/daar-waar-we-geen-ogen-hebben

De Today serie is een reeks schilderijen; op elk schilderij staat een datum in wit tegen een met kleur ingevulde achtergrond (meestal een grijstint, soms ook blauw of rood). De code die Kawara hanteert is de taal van het land waar hij zich die dag bevindt. Lukt het hem niet om het schilderij op die dag te voltooien, dan vernietigt hij het. Elk doek wordt bewaard in een doos met een dagblad van de betreffende dag.

Kawara speelt de datum tegen zichzelf uit; hij toont de mogelijkheden en de onmogelijkheden van een bepaalde dag. Hij toont de dag als werk en als context van verder niet duidelijk gemaakte persoonlijke ervaringen en herinneringen. Hij gebruikt het museum waar de werken hangen, als een adequate, want neutrale archiefruimte.

Op een subtiele en tegelijkertijd scherpe manier verwijst Kawara naar het leven buiten het kunstwerk en buiten het museum, zoals hij ook vaak niet op een opening van zijn tentoonstellingen verscheen, op een verzoek of op een enquête reageerde met het sturen van een telegram met de tekst I am still alive.

On Kawara, One Million Years, 1969

www.stedelijk.nl/nl/collectie/10699-on-kawara-one-million-years

Een man en een vrouw, naast elkaar gezeten, lezen jaartallen die beginnen 1 miljoen jaar vóór 1969 (het jaar dat dit werk gemaakt werd) en die doorgaan tot 1 miljoen jaar na 1969. Ik heb in het Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam meerdere malen aan de uitvoering van deze ‘partituur’ meegedaan en vond het een bijzondere ervaring. Tijdens het lezen werd ik mij er bijvoorbeeld van bewust hoe snel een bezoeker door de ruimte liep, of hoe lang hij op een bepaalde plek bleef staan om te luisteren. Ik voelde hoe ik met mijn leespartner de tijd segmenteerde en ritmeerde, omdat je samen onvermijdelijk een cadans van spreken creëert. Ik had niet verwacht dat iets doen dat in zo hoge mate naar zichzelf verwijst, ook naar zijn omgeving gaat verwijzen. Dat iets dat zo kaal is, tot een ritueel en een bezwering kan worden. Ook de begin- en eindpunten van de lezingen staan als bijzondere gebeurtenissen in mijn geheugen gegrift.

Roman Opalka (1931-2011), 1965 / 1 – ∞

www.opalka1965.com

De Pools-Franse schilder Opalka begon in 1965 een reeks schilderijen, alle van hetzelfde formaat, met regels van achter elkaar geschilderde cijfers. Hij begon met het cijfer 1 en op zijn laatste schilderij was hij gekomen tot het cijfer 5.607.249 Bovendien maakte Opalka elke dag gedurende 46 jaar een fotografisch zelfportret. Ook liep er een geluidsband mee die registreerde hoe hij elk cijfer dat hij schilderde, uitsprak. Nadat hij eerder andersoortige werken over tijd had gemaakt, kwam hij tot dit immense totaalproject, waarvan elk schilderij een ‘detail’ is. ‘All my work is a single thing, the description from number one to infinity. A single thing, a single life.’ en ‘The problem is that we are, and are about not to be.’ In de loop van zijn project gebruikte hij een steeds lichtere achtergrond om zijn cijfers op te schilderen, eindigend met wit op wit. Zijn laatste schilderij is weliswaar onvoltooid, maar voltooit zijn oeuvre.

Tot slot twee opmerkingen.

Ik twijfel aan wat vaak gezegd wordt: kunst laat ons de werkelijkheid op een nieuwe manier zien. Als dit werkelijk waar is, als dit nieuwe zou beklijven, had kunst al lang de wereld veranderd en had kunst niet tot amusement en tot een consumptie-artikel kunnen worden.

Ik neem liever een minder absoluut standpunt in – ik ben van mening dat wat de kunst in, bijvoorbeeld, het veld van de tijd naar boven haalt, vaak al aanwezig was en een sluimerend bestaan leidt. Niemand heeft immers een encyclopedisch overzicht van wat de mens of de mensheid weet; ook wat wij (nog) niet weten en wat wij nog moeten leren (ook al is het bekend) ervaren wij als nieuw. Kunst is nooit in overeenstemming met welke tijdlijn dan ook.

Zeker is wat mij betreft: kunst gaat in op wat ons tot mensen maakt, op onze geschiedenis, op onze herinneringen, op wat wij vergeten zijn, op wat onze culturele evolutie is.

De mantra van het nieuwe en de toekomst in de kunst maakt ons, zoals het er nu voorstaat, tot consumenten van kunst. Maar kunst heeft een langere adem en is belangrijk wat betreft het onthouden en terughalen van wat wij weten of hadden kunnen weten. Dat maakt kunst tot een existentiële factor van de eerste orde. Wij zijn cultuurwezens en wij moeten ons zelf blijven uitdagen. Kunst daagt ons uit.

Dat gegeven maakt elke strategie die onze kennis en onze waarden de-construeert en re-construeert, belangrijk. De deconstructie die wij in de kunst tegenkomen en die ons uitdaagt, is wat dit betreft vergelijkbaar met een psychoanalyse van de culturele constructies waarmee wij leven en waarin wij geloven – zoals tijd, ruimte, identiteit, ideologie, perspectief, werk, liefde, levenservaring.

Dat maakt het persoonlijke werk dat kunstenaars in hun ateliers doen, tot iets dat ook politiek is. Politiek is, letterlijk, wat er in de stad waarin wij samenleven, gebeurt. Politiek is een vorm van ecologie. Het persoonlijke is politiek, het politieke is persoonlijk. Waar heb ik dat eerder gehoord? Het is de erfenis van de revoltes van 1968 waaraan wij nu in 2018 terugdenken.

INZOOMEN

GERRIT HOOGSTRATENU kent allemaal wel die filmpjes, bij sommige reclames bijvoorbeeld, of aan het begin van speelfilms, waarbij we van ergens diep uit de ruimte in duizelingwekkende vaart op onze eigen planeet afstormen. We passeren galactische stelsels, naderen de Melkweg, duiken erin en voelen de nevels van sterren langs ons lichaam strijken, realiseren ons in een flits van bewustzijn dat elke ster ook een zon is net als onze eigen zon, met planeten waar misschien leven mogelijk is, maar geen tijd om daar lang bij stil te staan, daar vliegen we al ons eigen sterrenstelsel in, ontwijken de ringen rond Jupiter om ons niet aan de scherpe randen te snijden, blozen bij het zien van de rode planeet, en dan, we gaan bijna huilen van geluk, is daar moeder aarde, onze eigen blauwe planeet.

We duiken de atmosfeer in, de contouren van de continenten tekenen zich af in de blauwe watervlakte, de van Bretagne afgebroken krijtrotsen lichten op aan de Engelse kustlijn, een veerboot trekt haar spoor door het Noordzeekanaal, en daar is het dan, dat kleine landje met zijn polders, de Waddeneilanden, de rechte slootjes in het verkavelde land, het IJsselmeer en de Afsluitdijk, het fort van Pampus, de Randstad en ja hoor Amsterdam en de grachtengordels en steeds preciezer de buurt waar we zelf wonen, daar is onze straat, daar is ons huis, daar ons balkon, en op dat balkon, lekker in het zonnetje in haar bikini, onze vriendin… in de armen van een ander.

Maar voor we nu woedend verhaal gaan halen, of verdrietig en diep teleurgesteld, maar net wat in onze aard ligt, raad ik u aan eerst nog eens even goed te kijken. Zeker, zij is het, onze vriendin, in haar bikini en in de armen van een ander, maar ze lijkt hier wel een heel stuk jonger dan nu, of nee, ze ís een heel stuk jonger dan nu. En die ander, dat is dat vriendje van vroeger waar ze ons allang over heeft verteld, leuke jongen maar het was de ware niet.

Wat is hier nu aan de hand? Hoe kan het dat we zo in het verleden kijken?

In die filmpjes gebeurt dat natuurlijk helemaal niet, maar dat zou eigenlijk wel moeten, want als je inzoomt op dat balkon van zo ver weg, van zo diep uit de ruimte, dan zou onze vriendin in feite uitkijken op de toendra die wat nu de Britse eilanden zijn aan het vaste land verbond, en ze zou ook niet op een balkon zitten maar op de rug van een goeiige mammoet. In die filmpjes zit namelijk een ernstige gedachtefout. En dat heeft u natuurlijk ook allang door.

Want als wij ’s nachts naar de sterren kijken, zegt u tegen mij, dan zien we het licht dat ze uitstralen. Dat licht heeft er jaren over gedaan om ons te bereiken, lichtjaren noemen we die. En licht reist met een snelheid van 300.000 km per seconde. In een minuut is dat 18 miljoen kilometer, dat wil dus zeggen dat de dichtstbijzijnde ster, de Proxima Centauri, op een afstand van 4,3 lichtjaar tot de aarde staat, het beeld dat wij zien heeft er dus 4,3 jaar over gedaan om ons oog te bereiken. En u kunt mij dan ook zo zeggen dat het licht van de naaste buur van ons melkwegstelsel, de Andromedanevel, daar 2,2 miljoen jaar geleden vertrok. Ik leer echt veel van u vandaag, dat is altijd zo fijn als je zelf niet zoveel weet. Maar nu u mij dat allemaal heeft verteld, ga ik er toch nog even verder over nadenken.

Als ik het nu goed begrijp dan kijken we dus, als we onze telescopen op de ruimte richten, terug in de tijd. Wat we zien is het verleden. Een ster ontzettend ver weg, zeg ik nu maar even in mijn eigen woorden, kan in feite al ontploft zijn, of geïmplodeerd tot een zwart gat, of met een andere ster zijn samengesmolten tot een supernova. We kunnen het heden van die ster gewoon niet zien, omdat die te ver van ons af staat en omdat de snelheid van het licht, hoe ongelooflijk snel ook, toch nog steeds niet zo snel is dat het heden van die ster ons op hetzelfde moment bereikt. En dat is maar goed ook, want dan had die vriendin ons alsnog wel wat uit te leggen.

Maar nu ga ik proberen dat eens om te draaien en vanuit die ster terug te kijken naar onze aarde. Ik noemde net al het woord inzoomen. Stel je nu eens voor dat op onze dichtstbijzijnde ster, die Proxima Centauri, dat daar een telescoop zou staan met zo’n ongelooflijk sterke zoomlens dat die in staat zou zijn de aarde zo dichtbij te halen dat je er de balkons van de huizen zou kunnen zien. En dat in een mum van tijd, gewoon even aan de lens draaien en hup, daar zit ze. Het fascinerende van die gedachte vind ik dat je dan dus rechtstreeks in ons eigen verleden zou kijken, in dit geval dat van precies 4,3 jaar geleden. In de tijd blijft immers alles bewaard, maar omdat tegelijkertijd voor onze normale waarneming ook alles vloeit en niets blijft, gaat direct ook alles weer verloren. Natuurlijk, we hebben ons geheugen, we herinneren ons, maar zou het niet leuk zijn als we die hele map vol films en foto’s vanuit de ruimte bezien gewoon open zouden kunnen slaan en tot leven brengen?

Als ik die woorden zeg, films en foto’s, komt het misschien al wat dichterbij. Dat zijn precies de media waarmee wij gebeurtenissen in de tijd vastleggen, althans, sinds de uitvinding van de camera. Maar dat vastleggen hebben we op het moment zelf gedaan, en we kunnen alleen naar die vastgelegde beelden kijken door ze nog eens af te spelen of door nog eens door een album te bladeren. Kijken we naar een gebouw, of zelfs een monument, of als u de moeite neemt wat verder te reizen, een piramide, dan ervaren we emotioneel wel degelijk iets van de lange tijd geleden dat die piramide ontstond, en we verwonderen ons over het feit dat men toen in staat was zoiets te bouwen, maar we kunnen de bouw zelf niet zien. We kunnen die wel archeologisch onderzoeken, en er zijn door kunstenaars in die tijd ook afbeeldingen van gemaakt, antieke stripverhalen, mede aan de hand daarvan kunnen we ons wel vrij nauwkeurig voorstellen hoe het allemaal in zijn werk is gegaan, maar stel je nou eens voor dat je precies het punt in de ruimte zou kunnen berekenen waar je een telescoop zou moeten zetten die inzoomt en scherp stelt op exact het moment dat de deksteen wordt geplaatst. Dat zou toch fantastisch zijn! U merkt wel dat bij het hele idee in elk geval mijn verbeelding volledig op hol slaat.

Ik zou dan bijvoorbeeld graag eens met eigen ogen willen zien hoe de filosoof Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel op 13 oktober 1806, voor aanvang van de slag bij Jena, Napoleon Bonaparte op zijn paard voorbij ziet komen. Misschien zou ik op zijn gezicht kunnen lezen wat er op dat moment door hem heen ging. Er bestaat een zwart wit illustratie van deze ontmoeting, een tekening in Oost-Indische inkt als ik het goed heb, gemaakt voor een nummer van Harpers Magazin uit 1895, bijna negentig jaar na dato dus. Wat me daarin treft is niet zozeer Hegel die met een dik boek onder de arm, waarschijnlijk de Phenomenologie des Geistes, langs de weg staat, maar het paard waarop Napoleon zit. Napoleon had iets met paarden, allemaal schimmels, en klein van stuk, kleine witte paarden waarop hij zelf wat groter leek. Het dier kijkt trots en tevreden om zich heen, heeft het duidelijk naar zijn zin, machthebber en paard versterken elkaars positie. Waar doet u dit aan denken? Inderdaad, Poetin met ontbloot bovenlijf op een paard, het beeld komt voor de trouwe radio 4 luisteraars regelmatig voorbij in een reclame voor het Aids fonds.

Als we nu onze telescoop 83 lichtjaar dichterbij zetten, kunnen we inzoomen op nog zo’n scène die deel uitmaakt van ons collectief geheugen: Turijn, 3 januari 1889. Een oud en kreupel paard wordt afgeranseld door zijn koetsier, en Friedisch Nietszche kan het niet aanzien. Hij heeft zo’n medelijden met het arme dier dat hij het snikkend om de hals vliegt om even later zelf op slag krankzinnig ter aarde te storten. Het verhaal is in de wereld gebracht door Erich Podach, in 1930, die heeft daar dus vanuit een punt in de tijd 41 jaar later op ingezoomd. Hij beweert dan dat het verhaal in Turijn mondeling is overgeleverd tot het hem bereikte, maar volgens velen heeft hij het hele verhaal gewoon uit de duim gezogen. Maar is dat erg? Moet de wereld zoals kunstenaars die ons laten zien één op één kloppen met de werkelijkheid?

Het zijn zo mijn associaties en overwegingen bij het thema van deze Kunst aan de Schinkel. Ik draai maar wat aan de lenzen en soms beeft mijn hand een beetje en als je dan zo sterk inzoomt krijg je rare verschuivingen. Maar langzamerhand, bij het schrijven van dit stuk, doemde voor mij het paard op dat u allemaal kent en waarop is ingezoomd door een van de grootste kunstenaars die wij kennen. Wat zou het niet leuk zijn om live de beelden te kunnen volgen hoe dat paard is ontstaan. Waar in de ruimte moet ik mijn telescoop zetten om precies dat moment te kunnen zien waarop Pablo Picasso zijn kermend paard van Guernica schildert. We zoomen in op Parijs, voorjaar 1937, Picasso heeft de opdracht gekregen een wand vullend schilderij te maken voor het Spaanse paviljoen van de wereldtentoonstelling en hij weet niet wat hij moet maken, hij heeft werkelijk geen idee, geen inspiratie, tot op 26 april 1937 het Baskische dorpje Guernica wordt plat gebombardeerd door Duitse bommenwerpers die Franco een handje komen helpen. De rest is geschiedenis, Picasso schildert zijn beroemde meesterwerk. Met dat paard. Maar dat paard stond er eerst helemaal niet op. In het middendeel was eerst een zon getekend, die wist hij op een bepaald moment uit en dan verschijnt daar ineens dat in doodsnood schreeuwende paard.

Natuurlijk bestaat er geen telescoop in de ruimte waarmee ik op de totstandkoming van de Guernica kan inzoomen, behalve dan in mijn fantasie, en nu misschien ook een beetje in de uwe. Toch heb ik wel degelijk dat hele proces in beeld gebracht gezien. Een van Picasso’s vriendinnen uit die tijd, de fotografe Dora Maar, heeft het namelijk van dag tot dag met haar camera vastgelegd en die foto’s zijn te bewonderen in Parijs. In Musée Montmartre om precies te zijn, ik was daar een paar maanden geleden en ik moest daar nu eigenlijk meteen aan denken. Wat zij heeft vastgelegd is niet alleen de totstandkoming van dat schilderij, maar ook de wijze waarop Picasso door zijn denkbeeldig telescoop keek. Hij hoefde die niet heel ver van de aarde weg te zetten, een paar lichtweken hooguit, de wereldtentoonstelling opende 25 mei, nog geen maand dus na het bombardement op Guernica.

Dat paard van Picasso maakt een onuitwisbare indruk op iedereen die het ziet, je hoort het angstig hinniken, maar tegelijkertijd is het ook een heel abstract paard, er zitten rare verschuivingen in, er is nogal apart op ingezoomd.

En daarmee kom ik tot een voorzichtige conclusie: kunstenaars hebben hun verbeelding en die zou je kunnen vergelijken met een telescoop in de ruimte waarmee ze inzoomen op onze werkelijkheid. Het mooie, bevrijdende, poëtische en misschien ook vervreemdende van de manier waarop ze dat doen, is dat ze ons, en trouwens ook zichzelf, niet per se willen laten zien wat wij gewend zijn te zien, maar daar juist een beetje van afwijken. Het paard van Picasso klopt niet, toch is het de essentie van wat een paard is. Denk de tijd weg en het is ook een paard van alle tijden.

Misschien is dat wat beeldend kunstenaars ieder op hun eigen wijze doen, als ze de tijd loslaten: inzoomen. En misschien is inzoomen dan een vorm van tijdreizen waarbij geen tijd verloren gaat, die amper tijd kost, alleen de duur van de handeling van het inzoomen. En dan gaat het niet alleen om wat zij ons laten zien, maar ook, en misschien wel vooral, om hoe zij dat doen, om hoe zij voor ons in beeld brengen wat zij vanuit hun wonderlijke positie in de ruimte van hun verbeelding hebben waargenomen. Inclusief alle bevingen en harstochten en emoties die ze zelf bij het kijken hebben ervaren. En zo kan het gebeuren dat twee geliefden, misschien wel onze vriendin van het balkon met haar huidige minnaar, op elkaar, nee, niet liggen, maar zweven. Of dat een stuk plastic boven een koraal geen vervuiling maar een nieuwe exotische vissoort lijkt. Of dat licht en geluid Kaleidoscopisch samenvallen tot een buurtheiligdom. Of dat kringen in een zandbak door de silhouetten van een opa en zijn verbaasde kleinzoon worden aangezien voor tekens van een buitenaardse beschaving. Het zijn maar een paar voorbeeldjes uit de kunst die u hier bij deze Kunst aan de Schinkel kunt gaan zien. Kunst gemaakt door kunstenaars die hier bij u om de hoek wonen. Ze zijn onder ons, dames en heren. En laten we daar blij mee zijn.

NINA GLÖCKNER - WRAPPING UP - FINISSAGE

CEES DE BOERFor the finissage of KadS 2018 curator Marisol Ferradás developed a special event together with performance artist Nina Glöckner, at the so-called End-Point Shed, the little house near the tracks of the Historical Electric Tram Museum at Havenstraat. The shed itself seems a happenstance work of art, a collage of vintage building materials. Inside it, Kubra Khademi did her performance Spidering for the opening of KadS and left its result there as an installation.

Using the same material as Khademi, Glöckner wrapped a long white rope around the little house. Following the rectangular shape of the shed, a contrast was created with Khademi’s web inside which explodes in all directions and seems to want to escape the dimensions of the inside space. Glöckner symbolically nailed her weaving of ropes to the ground, to anchor the house to its location. Two performances, two symbolic structures result in one installation full of meaningful contrasts. The inside space is about Khademi’s personal biography; the outside of the little house now is more about preserving and protecting it and what it contains.

Today the location at Havenstraat is one of the last remaining fringe area’s of the city of Amsterdam. Once the point where the city, the Schinkel and the Amsterdam Forest met, creating a hub to travel to Amstelveen and Haarlemmermeer, it now has shifted position and has almost become part of the city’s centre. The provisional, shanty buildings, housing small enterprises, now happen to stand on very expensive grounds. This creates a big problem for the Museum Tram Society, its shanty halls housing the collection of historical trams from Amsterdam, Prague and Vienna. The volunteers who maintain and keep the trams running, essentially keep an important and fun part of the collective memory of the city alive.

The future of the Havenstraat location seems to have been decided on: more apartment buildings to be developed. Another case of gentrification – exactly the socio-economic process pointed at critically by Hertog Nadler’s installation Double Take, a Neighbourhood Real Estate for KadS 2018. An example of spontaneous city evolution will be erased. With their ropes Kubra Khademi and Nina Glöckner will not be able to prevent this; but the joined and powerful image of their performances will tell the story for some time to come.

WHEN THE NOTION OF TIME DISAPPEARS

KadS 2018 [Kunst aan de Schinkel]

From 22 April through 3 June 2018, Soledad Senlle Art Foundation presents the fourth edition of KadS [Art at the Schinkel]: WHEN THE NOTION OF TIME DISAPPEARS. Art manifestation KadS draws attention to art works in the public space, at special and unexpected spots in the area around the river Schinkel. Some ten [inter]national artists have been invited to investigate and illustrate their reaction to the question: What happens when the notion of time disappears? Starting 22 April, the public can expect to see works by Tamar Frank, Popel Coumou and Hertog Nadler, among others, in this Amsterdam neighbourhood.

More and more, our lives are controlled by the sense that time slips by irrevocably, that we need to make use of time in a responsible way. But what happens when the notion of time disappears? In what kind of dimension do we find ourselves? And what is the past, what the future? Or can we make this distinction no longer? And how do we achieve a state of timelessness?

The Schinkel neighbourhood

Anno 2018, the concepts of time and timelessness are simultaneously intertwined and at battle. In this ‘commonplace’ environment, how do time and space relate to each other? What are the factors influencing this process? Our own memory or that of others? Sounds, the moment of the day or the change of seasons… The artists involved in the project could play a special role as investigators of the notion of time, and they might even be able to make time stand still or disappear, albeit for a very brief moment…

Poetical interventions

Popel Coumou works as a sculptor with light in the showroom at the David Lloyd fitness centre on Overtoom. Time appears to be standing still in her spaces that don’t exist. Eva Gonggrijp takes the visitor with her to a special era in a virtual experience. Henk Schut records sounds in and round the water of the Schinkel – he integrates the recordings into a multi-media audio installation in which the sound is moving continuously. The ‘closed’ cemetery Huis te Vraag is especially a place dominated by a sense of timelessness. As the manager, Leon van de Heijden, says: ‘It’s a miracle that it still exists’. This spring temporary and site-specific art works function as poetical interventions in the Schinkel neighbourhood.

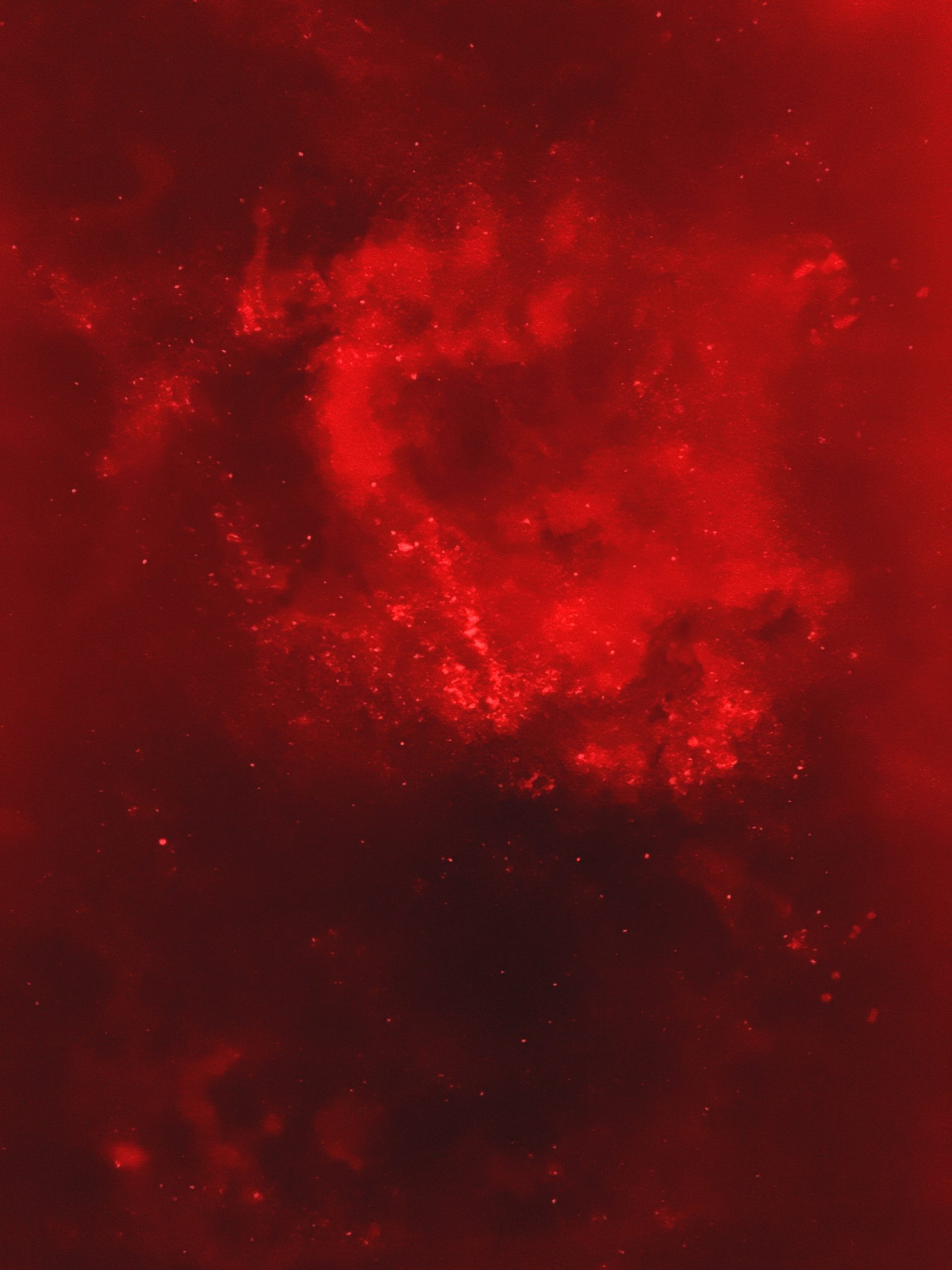

Kaleidoscope under the bridge

In the huge cellar under the bridge, at the crossing of the river Schinkel and Zeilstraat, the spectacular work of Dutch artist Tamar Frank can be observed. A spot where the public is not allowed in normal circumstances. Here, especially for Art at the Schinkel, Frank creates a hypnotizing space through the installation of a life-size kaleidoscope in an attempt to enable people to experience a sense of timelessness.

Participating artists

Aeneas Wilder [UK], André Pielage [NL], Eva Gonggrijp [NL], Henk Schut [NL], Hertog Nadler [Chaja Hertog NL & Nir Nadler IL], Kubra Khademi [AF], Popel Coumou [NL], Sarah Engelhard [NL], Semâ Bekirovic [NL], Tamar Frank [NL]

Team

Curator: Marisol Ferradás

Assistent curator: Doina Kraal

Project coördinator: Claartje Kortbeek

PR: Marleen Kers

With thanks to Sascia Vos for her contribution

KadS is made possible with the generous support of: Mondriaan Fonds – AFK- Gemeente Amsterdam – Soledad Senlle B.V.

With thanks to: AVRO/TROS – WeMakeVR – AWAYIN – Pieter Janssen- Mylène Verdurmen – Centercom – RVE V&OR – Waternet – Ton Overmars – Kei Omura/Atelier Riota [Japan], Beldock

Kubra Khademi (AF) END-POINT, 2018

Performance and installation,

Havenstraat 1, Amsterdam

Kubra Khademi enters the confined space of a small shed, Eindpunt* at the Haarlemmermeer tram station,bringing a long thin rope with her. She then starts

weaving a web in all directions and slowly fills up all of the available space. Meanwhile, in her mind she reaches back to the tapestry weaving she was obliged to occupy

herself with as a young child, back in Afghanistan where she was born. She continues weaving her web until she is imprisoned by it, unable to move or act.

Through a spatial metaphor, the woman performing End-Point repeats and embodies a personal childhood drama that many other girls will relate to. Due to the endless work at the weaving loom, she lost a lot of space/time during which she could have developed differently. She could have been moving around freely and play, learn, grow and spread her wings.

It is said that the confines of what language allows us to say also constitute the limits of what we are able to understand of our world. This, however, implies a disregard of the fact that we also understand our world through our bodily senses: we experience, observe, learn and understand beyond the words, beyond all the other instruments we manipulate.

Khademi’s weaving performance and woven installation in the shed has a claustrophobic effect. Her senses are imprisoned as well as her body. She is cut off from the experience of her personal space/time as it resides within her body. Immersing yourself in your personal history chases away the time that others took from you and makes room for the space/time that is truly yours. Is Khademi repeating this drama in order to once more taste the (im)possible desires she entertained so long ago? To communicate what turned her into the politically motivated person she is now?

Kubra ( AF, 1989) – Lives, works and studies in Paris – Panthéon Sorbonne (Paris), School of Visual Arts and Design (Lahore, Pakistan) Exhibitions: Palais de Tokyo (Paris), Queens Museum & Knockdown Center (New York), Kasteel van Gaasbeek (Brussel), Silkroad Gallery (Tehran), Museum of History of Immigration (Paris)

Kubra Khademi (AF) END-POINT, 2018

Performance and installation,

Havenstraat 1, Amsterdam

Kubra Khademi enters the confined space of a small shed, Eindpunt* at the Haarlemmermeer tram station,bringing a long thin rope with her. She then starts

weaving a web in all directions and slowly fills up all of the available space. Meanwhile, in her mind she reaches back to the tapestry weaving she was obliged to occupy

herself with as a young child, back in Afghanistan where she was born. She continues weaving her web until she is imprisoned by it, unable to move or act.

Through a spatial metaphor, the woman performing End-Point repeats and embodies a personal childhood drama that many other girls will relate to. Due to the endless work at the weaving loom, she lost a lot of space/time during which she could have developed differently. She could have been moving around freely and play, learn, grow and spread her wings.

It is said that the confines of what language allows us to say also constitute the limits of what we are able to understand of our world. This, however, implies a disregard of the fact that we also understand our world through our bodily senses: we experience, observe, learn and understand beyond the words, beyond all the other instruments we manipulate.

Khademi’s weaving performance and woven installation in the shed has a claustrophobic effect. Her senses are imprisoned as well as her body. She is cut off from the experience of her personal space/time as it resides within her body. Immersing yourself in your personal history chases away the time that others took from you and makes room for the space/time that is truly yours. Is Khademi repeating this drama in order to once more taste the (im)possible desires she entertained so long ago? To communicate what turned her into the politically motivated person she is now?

Kubra ( AF, 1989) – Lives, works and studies in Paris – Panthéon Sorbonne (Paris), School of Visual Arts and Design (Lahore, Pakistan) Exhibitions: Palais de Tokyo (Paris), Queens Museum & Knockdown Center (New York), Kasteel van Gaasbeek (Brussel), Silkroad Gallery (Tehran), Museum of History of Immigration (Paris)

Kubra Khademi (AF) END-POINT, 2018

Performance and installation,

Havenstraat 1, Amsterdam

Kubra Khademi enters the confined space of a small shed, Eindpunt* at the Haarlemmermeer tram station,bringing a long thin rope with her. She then starts

weaving a web in all directions and slowly fills up all of the available space. Meanwhile, in her mind she reaches back to the tapestry weaving she was obliged to occupy

herself with as a young child, back in Afghanistan where she was born. She continues weaving her web until she is imprisoned by it, unable to move or act.

Through a spatial metaphor, the woman performing End-Point repeats and embodies a personal childhood drama that many other girls will relate to. Due to the endless work at the weaving loom, she lost a lot of space/time during which she could have developed differently. She could have been moving around freely and play, learn, grow and spread her wings.

It is said that the confines of what language allows us to say also constitute the limits of what we are able to understand of our world. This, however, implies a disregard of the fact that we also understand our world through our bodily senses: we experience, observe, learn and understand beyond the words, beyond all the other instruments we manipulate.

Khademi’s weaving performance and woven installation in the shed has a claustrophobic effect. Her senses are imprisoned as well as her body. She is cut off from the experience of her personal space/time as it resides within her body. Immersing yourself in your personal history chases away the time that others took from you and makes room for the space/time that is truly yours. Is Khademi repeating this drama in order to once more taste the (im)possible desires she entertained so long ago? To communicate what turned her into the politically motivated person she is now?

Kubra ( AF, 1989) – Lives, works and studies in Paris – Panthéon Sorbonne (Paris), School of Visual Arts and Design (Lahore, Pakistan) Exhibitions: Palais de Tokyo (Paris), Queens Museum & Knockdown Center (New York), Kasteel van Gaasbeek (Brussel), Silkroad Gallery (Tehran), Museum of History of Immigration (Paris)

Henk Schut (NL) UNTITLED, 2018

Sound installation,

Sloterkade 171, Amsterdam

The installation by Henk Schut in Soledad Senlle’s exhibition space can be interpreted as a reaction to Heraclitus’ famous saying: ‘one cannot step into the same river twice.’ In ancient Greece as in present day Amsterdam, giving a name to a river is like trying to constrain the water within its bed or within the brick walls of the city. Moreover, here embankments and bridges stand on tall stilts that reach deep down below the groundwater to find stability. Under the tarmac and the tiles are the tides. Walking on firm ground is almost an illusion in this city. Schut’s installation addresses the senses of hearing and seeing…

Underwater recordings of the river Schinkel are distributed around the space at Soledad Senlle Art Foundation. Metal slabs looking like warped and frozen mirrors on the gallery walls, act as speakers. During the six weeks of the exhibition a computer program creates an ongoing soundscape. It is Schut’s intention to avoid any recognizable structure or attention curve, so as to make the soundscape timeless. The computer uses a specially designed algorithm that decides which of the 25 different speakers in the space is activated.

In the installation Schut creates an environment in which new patterns are constantly generated. Randomly distributed silences are important within the soundscape, they are like moments of breathing outside of the water, before the never ending story of the river continues. Silences enhance the disappearance of time and space. Almost like an echo in your body, they create the possibility to see and hear what just happened, before the river takes over again.

Henk Schut [NL, 1957] – Lives and works in Amsterdam – AHK [Amsterdam] – Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts [London] Exhibitions: Van Gogh Mile [Amsterdam], Vesalius A Requiem[Bologna] – Director: Maki Ishii, Tojirareta Fune/The Sealed Ship [Utrecht, Berlin, Tokyo]

Henk Schut (NL) UNTITLED, 2018

Sound installation,

Sloterkade 171, Amsterdam

The installation by Henk Schut in Soledad Senlle’s exhibition space can be interpreted as a reaction to Heraclitus’ famous saying: ‘one cannot step into the same river twice.’ In ancient Greece as in present day Amsterdam, giving a name to a river is like trying to constrain the water within its bed or within the brick walls of the city. Moreover, here embankments and bridges stand on tall stilts that reach deep down below the groundwater to find stability. Under the tarmac and the tiles are the tides. Walking on firm ground is almost an illusion in this city. Schut’s installation addresses the senses of hearing and seeing…

Underwater recordings of the river Schinkel are distributed around the space at Soledad Senlle Art Foundation. Metal slabs looking like warped and frozen mirrors on the gallery walls, act as speakers. During the six weeks of the exhibition a computer program creates an ongoing soundscape. It is Schut’s intention to avoid any recognizable structure or attention curve, so as to make the soundscape timeless. The computer uses a specially designed algorithm that decides which of the 25 different speakers in the space is activated.

In the installation Schut creates an environment in which new patterns are constantly generated. Randomly distributed silences are important within the soundscape, they are like moments of breathing outside of the water, before the never ending story of the river continues. Silences enhance the disappearance of time and space. Almost like an echo in your body, they create the possibility to see and hear what just happened, before the river takes over again.

Henk Schut [NL, 1957] – Lives and works in Amsterdam – AHK [Amsterdam] – Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts [London] Exhibitions: Van Gogh Mile [Amsterdam], Vesalius A Requiem[Bologna] – Director: Maki Ishii, Tojirareta Fune/The Sealed Ship [Utrecht, Berlin, Tokyo]

Henk Schut (NL) UNTITLED, 2018

Sound installation,

Sloterkade 171, Amsterdam

The installation by Henk Schut in Soledad Senlle’s exhibition space can be interpreted as a reaction to Heraclitus’ famous saying: ‘one cannot step into the same river twice.’ In ancient Greece as in present day Amsterdam, giving a name to a river is like trying to constrain the water within its bed or within the brick walls of the city. Moreover, here embankments and bridges stand on tall stilts that reach deep down below the groundwater to find stability. Under the tarmac and the tiles are the tides. Walking on firm ground is almost an illusion in this city. Schut’s installation addresses the senses of hearing and seeing…

Underwater recordings of the river Schinkel are distributed around the space at Soledad Senlle Art Foundation. Metal slabs looking like warped and frozen mirrors on the gallery walls, act as speakers. During the six weeks of the exhibition a computer program creates an ongoing soundscape. It is Schut’s intention to avoid any recognizable structure or attention curve, so as to make the soundscape timeless. The computer uses a specially designed algorithm that decides which of the 25 different speakers in the space is activated.

In the installation Schut creates an environment in which new patterns are constantly generated. Randomly distributed silences are important within the soundscape, they are like moments of breathing outside of the water, before the never ending story of the river continues. Silences enhance the disappearance of time and space. Almost like an echo in your body, they create the possibility to see and hear what just happened, before the river takes over again.

Henk Schut [NL, 1957] – Lives and works in Amsterdam – AHK [Amsterdam] – Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts [London] Exhibitions: Van Gogh Mile [Amsterdam], Vesalius A Requiem[Bologna] – Director: Maki Ishii, Tojirareta Fune/The Sealed Ship [Utrecht, Berlin, Tokyo]

Henk Schut (NL) UNTITLED, 2018

Sound installation,

Sloterkade 171, Amsterdam

The installation by Henk Schut in Soledad Senlle’s exhibition space can be interpreted as a reaction to Heraclitus’ famous saying: ‘one cannot step into the same river twice.’ In ancient Greece as in present day Amsterdam, giving a name to a river is like trying to constrain the water within its bed or within the brick walls of the city. Moreover, here embankments and bridges stand on tall stilts that reach deep down below the groundwater to find stability. Under the tarmac and the tiles are the tides. Walking on firm ground is almost an illusion in this city. Schut’s installation addresses the senses of hearing and seeing…

Underwater recordings of the river Schinkel are distributed around the space at Soledad Senlle Art Foundation. Metal slabs looking like warped and frozen mirrors on the gallery walls, act as speakers. During the six weeks of the exhibition a computer program creates an ongoing soundscape. It is Schut’s intention to avoid any recognizable structure or attention curve, so as to make the soundscape timeless. The computer uses a specially designed algorithm that decides which of the 25 different speakers in the space is activated.

In the installation Schut creates an environment in which new patterns are constantly generated. Randomly distributed silences are important within the soundscape, they are like moments of breathing outside of the water, before the never ending story of the river continues. Silences enhance the disappearance of time and space. Almost like an echo in your body, they create the possibility to see and hear what just happened, before the river takes over again.

Henk Schut [NL, 1957] – Lives and works in Amsterdam – AHK [Amsterdam] – Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts [London] Exhibitions: Van Gogh Mile [Amsterdam], Vesalius A Requiem[Bologna] – Director: Maki Ishii, Tojirareta Fune/The Sealed Ship [Utrecht, Berlin, Tokyo]

Aeneas Wilder (SCH) UNTITLED, 2018

Multidisciplinary installation,

Vondelpark, Amsterdam

Every single day during the KadS manifestation, volunteers using wooden tools make a drawing in the sand that covers the surface of a circular sculpture in the Vondelpark. They use instructions provided by artist Aeneas Wilder, but the drawing will be different every day.

Drawing in and making patterns with sand is as old as the world and is of all cultures. Every child likes to do this on the beach, right near the sea, and watches with excitement how his creation is sucked up by the waves. And then start all over again. Aeneas Wilder finds inspiration in the sophisticated sand and gravel gardens of Japanese Zen temples. These special places, meant to be used for contemplation, call up the essence of nature: emptiness, purity, repetition of the same. However, Wilder’s work also deals with transience, change, an identical pattern emerging every time as an individual image.

In this respect Wilder’s little Zen garden is more like a koan; a paradoxical question from the Zen master to his pupil, requiring an answer in the form of a word or an action. One of the best-known examples: What is the sound of one hand clapping? The drawing in the sandbox is changed, supplemented or erased by playing children, running dogs, the rain or the wind. Wilder: “The process of erasing a work of art is not in itself radical, but fundamental to the understanding of what art is and how it can contribute to the creative development of our lives. All things must pass away, and for a reason.”

Aeneas Wilder: [SCH, 1967] – Lives and works in Japan – Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design. Exhibitions: Chateau de Seneffe[Belgium] – Galerie Frank Taal [Rotterdam] – Villa Gustavanni [Bologna] –Warwick Arts Centre [Coventry]

Aeneas Wilder (SCH) UNTITLED, 2018

Multidisciplinary installation,

Vondelpark, Amsterdam

Every single day during the KadS manifestation, volunteers using wooden tools make a drawing in the sand that covers the surface of a circular sculpture in the Vondelpark. They use instructions provided by artist Aeneas Wilder, but the drawing will be different every day.

Drawing in and making patterns with sand is as old as the world and is of all cultures. Every child likes to do this on the beach, right near the sea, and watches with excitement how his creation is sucked up by the waves. And then start all over again. Aeneas Wilder finds inspiration in the sophisticated sand and gravel gardens of Japanese Zen temples. These special places, meant to be used for contemplation, call up the essence of nature: emptiness, purity, repetition of the same. However, Wilder’s work also deals with transience, change, an identical pattern emerging every time as an individual image.

In this respect Wilder’s little Zen garden is more like a koan; a paradoxical question from the Zen master to his pupil, requiring an answer in the form of a word or an action. One of the best-known examples: What is the sound of one hand clapping? The drawing in the sandbox is changed, supplemented or erased by playing children, running dogs, the rain or the wind. Wilder: “The process of erasing a work of art is not in itself radical, but fundamental to the understanding of what art is and how it can contribute to the creative development of our lives. All things must pass away, and for a reason.”

Aeneas Wilder: [SCH, 1967] – Lives and works in Japan – Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design. Exhibitions: Chateau de Seneffe[Belgium] – Galerie Frank Taal [Rotterdam] – Villa Gustavanni [Bologna] –Warwick Arts Centre [Coventry]

André Pielage (NL) SPONDE, 2018

Sculpture,

Vaartstraat, amsterdam

In the work of André Pielage, architecture is an important source of inspiration. For example, he transforms the vault of the chancel in Haarlem’s renowned St. Bavo into an autonomous sculpture. The construction of the supporting joists is reduced to an abstract line pattern and placed upside down on the floor. Instead of an architectonic apotheosis arching above the heads of the churchgoers like a firmament reflecting heavenly order, the vault now literally carries nothing. This kind of reversal brings another historical given to mind: the wooden ceilings of churches used to often be made by boat builders because they involve a similar construction as that of the rafters of a boat. In this context, Pielage’s title of the work, Sponde*, becomes more significant.

The vault, which is a boat as well as a bed, seduces one to associate this sculpture with the human body, but it might also trigger a memory of a performance in the past. And indeed, Pielage engages in performances too: in an old Utrecht yard cellar he would lie on his back on a tie rod between two walls for a long time, right under the vault supported by this rod. Or he would lie on his belly in a dilapidated little chapel, face down on a layer of earth under a Gothic arch which he pieced together from PVC tubes and corrugated board. Thus, the distinctions between high and low, up and down were blurred completely. Pielage is known to have expressed a desire to ‘be lying down separated from the ground’ – a longing to rise up from the earth by means of grounding. This desire to transcend from and skip space and time is given shape through the transformation of a church vault into a bed.

André Pielage (NL, 1975) – Lives and works in Rotterdam – University of the Arts (Utrecht) – Rijksakademie van beeldende kunsten (Amsterdam) Exhibitions: Kasteel van Gaasbeek (Brussel), Code Rood (Arnhem), Gallerí Gangur (Reykjavik), Center for Contemporary Art (Kitakyushu)

André Pielage (NL) SPONDE, 2018

Sculpture,

Vaartstraat, amsterdam

In the work of André Pielage, architecture is an important source of inspiration. For example, he transforms the vault of the chancel in Haarlem’s renowned St. Bavo into an autonomous sculpture. The construction of the supporting joists is reduced to an abstract line pattern and placed upside down on the floor. Instead of an architectonic apotheosis arching above the heads of the churchgoers like a firmament reflecting heavenly order, the vault now literally carries nothing. This kind of reversal brings another historical given to mind: the wooden ceilings of churches used to often be made by boat builders because they involve a similar construction as that of the rafters of a boat. In this context, Pielage’s title of the work, Sponde*, becomes more significant.

The vault, which is a boat as well as a bed, seduces one to associate this sculpture with the human body, but it might also trigger a memory of a performance in the past. And indeed, Pielage engages in performances too: in an old Utrecht yard cellar he would lie on his back on a tie rod between two walls for a long time, right under the vault supported by this rod. Or he would lie on his belly in a dilapidated little chapel, face down on a layer of earth under a Gothic arch which he pieced together from PVC tubes and corrugated board. Thus, the distinctions between high and low, up and down were blurred completely. Pielage is known to have expressed a desire to ‘be lying down separated from the ground’ – a longing to rise up from the earth by means of grounding. This desire to transcend from and skip space and time is given shape through the transformation of a church vault into a bed.

André Pielage (NL, 1975) – Lives and works in Rotterdam – University of the Arts (Utrecht) – Rijksakademie van beeldende kunsten (Amsterdam) Exhibitions: Kasteel van Gaasbeek (Brussel), Code Rood (Arnhem), Gallerí Gangur (Reykjavik), Center for Contemporary Art (Kitakyushu)

André Pielage (NL) SPONDE, 2018

Sculpture,

Vaartstraat, amsterdam

In the work of André Pielage, architecture is an important source of inspiration. For example, he transforms the vault of the chancel in Haarlem’s renowned St. Bavo into an autonomous sculpture. The construction of the supporting joists is reduced to an abstract line pattern and placed upside down on the floor. Instead of an architectonic apotheosis arching above the heads of the churchgoers like a firmament reflecting heavenly order, the vault now literally carries nothing. This kind of reversal brings another historical given to mind: the wooden ceilings of churches used to often be made by boat builders because they involve a similar construction as that of the rafters of a boat. In this context, Pielage’s title of the work, Sponde*, becomes more significant.

The vault, which is a boat as well as a bed, seduces one to associate this sculpture with the human body, but it might also trigger a memory of a performance in the past. And indeed, Pielage engages in performances too: in an old Utrecht yard cellar he would lie on his back on a tie rod between two walls for a long time, right under the vault supported by this rod. Or he would lie on his belly in a dilapidated little chapel, face down on a layer of earth under a Gothic arch which he pieced together from PVC tubes and corrugated board. Thus, the distinctions between high and low, up and down were blurred completely. Pielage is known to have expressed a desire to ‘be lying down separated from the ground’ – a longing to rise up from the earth by means of grounding. This desire to transcend from and skip space and time is given shape through the transformation of a church vault into a bed.

André Pielage (NL, 1975) – Lives and works in Rotterdam – University of the Arts (Utrecht) – Rijksakademie van beeldende kunsten (Amsterdam) Exhibitions: Kasteel van Gaasbeek (Brussel), Code Rood (Arnhem), Gallerí Gangur (Reykjavik), Center for Contemporary Art (Kitakyushu)

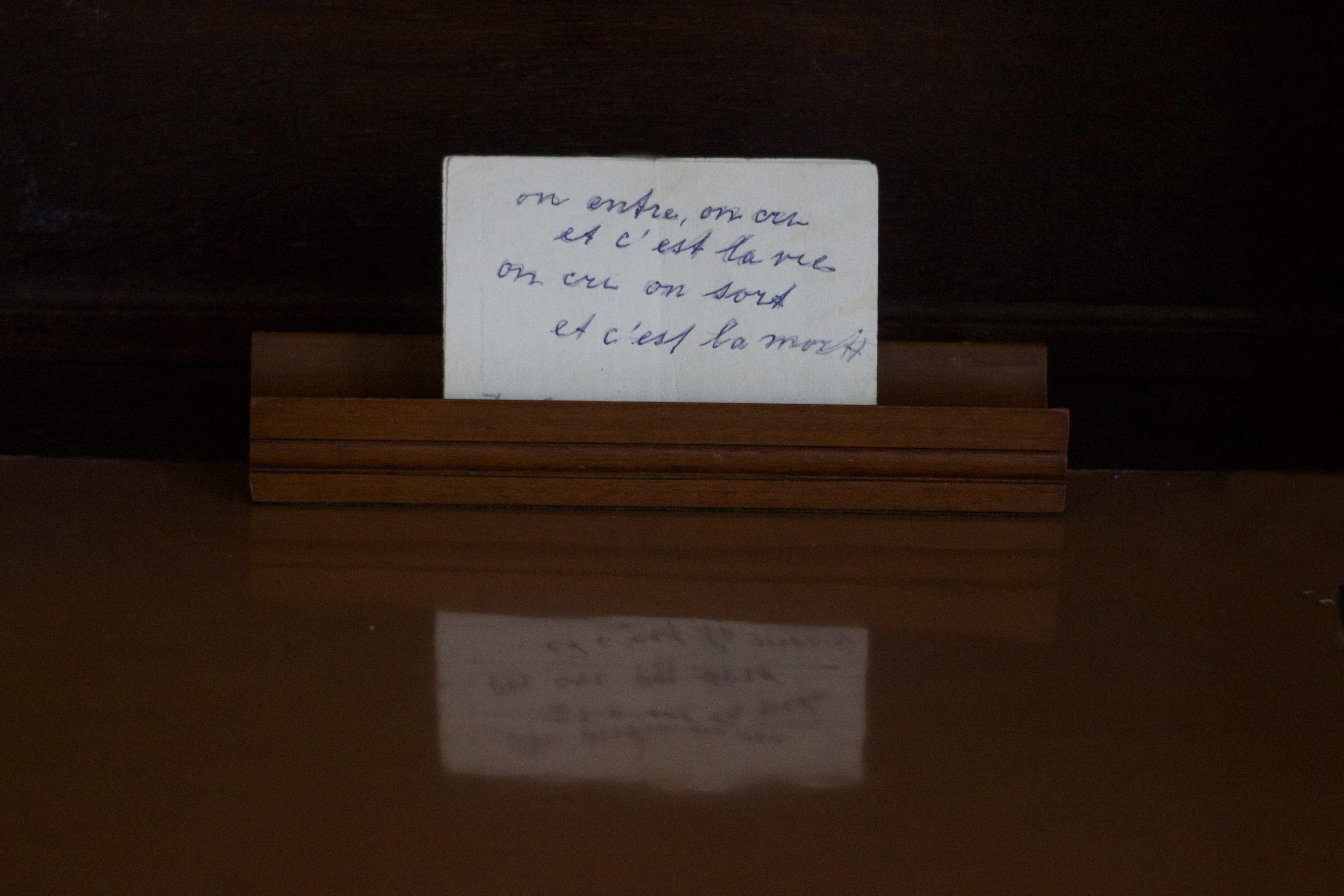

Eva Gonggrijp (NL) ON ENTRE, 2018

Multidisciplinary installation,

Sloterkade 171, Amsterdam

‘Once I dreamt that I walked through my old dollhouse, empty but full of atmosphere, waking up with a story, of which the words got lost’

Eva Gonggrijp

Memories want to be explored and recalled from the merciless passing by and disappearing, which is the essence of time. Memories do not agree with the one-way traffic of the time of the clock. They cling to other memories; if they venture back into times past, it is to move forward. Objects play a vital part in this. When you inherit precious objects, you do not inherit just the material, but also traces of people, memories of them and of particular situations, sometimes going back generations. There is nothing more lonely than a ring slipping off a finger with its destination unknown.

Gonggrijp’s grandmother built a dollhouse for her, the Eva Hof [Eva’s court], an almost perfect replica of her own house. A great part of her hidden past, her losses and dreams were echoed in the dollhouse. For Eva in turn, her grandmother’s house and the dollhouse in it became a safe haven, something to hold on to during a turbulent youth.

The technique of virtual reality enables Gonggrijp to wander around in her dream and share it with others. They are almost inaudible stories which dart out from the cracks of times past, from the space between things, from the silence in between the sounds. Who enters this space changes from subject to participating and direct object, since the traces of the past are not yours but do need your sensory perceptions to come to life.

Eva Gonggrijp [NL, 1960] – Lives and works in Amsterdam – KABK [Den Haag]. Exhibitions: Vleeshal [Haarlem], Gemeente Museum [Den Haag], Vishal [Haarlem], Arti et Amicitae [Amsterdam], Mediamatic [Amsterdam]

Eva Gonggrijp (NL) ON ENTRE, 2018

Multidisciplinary installation,

Sloterkade 171, Amsterdam

‘Once I dreamt that I walked through my old dollhouse, empty but full of atmosphere, waking up with a story, of which the words got lost’

Eva Gonggrijp

Memories want to be explored and recalled from the merciless passing by and disappearing, which is the essence of time. Memories do not agree with the one-way traffic of the time of the clock. They cling to other memories; if they venture back into times past, it is to move forward. Objects play a vital part in this. When you inherit precious objects, you do not inherit just the material, but also traces of people, memories of them and of particular situations, sometimes going back generations. There is nothing more lonely than a ring slipping off a finger with its destination unknown.

Gonggrijp’s grandmother built a dollhouse for her, the Eva Hof [Eva’s court], an almost perfect replica of her own house. A great part of her hidden past, her losses and dreams were echoed in the dollhouse. For Eva in turn, her grandmother’s house and the dollhouse in it became a safe haven, something to hold on to during a turbulent youth.

The technique of virtual reality enables Gonggrijp to wander around in her dream and share it with others. They are almost inaudible stories which dart out from the cracks of times past, from the space between things, from the silence in between the sounds. Who enters this space changes from subject to participating and direct object, since the traces of the past are not yours but do need your sensory perceptions to come to life.

Eva Gonggrijp [NL, 1960] – Lives and works in Amsterdam – KABK [Den Haag]. Exhibitions: Vleeshal [Haarlem], Gemeente Museum [Den Haag], Vishal [Haarlem], Arti et Amicitae [Amsterdam], Mediamatic [Amsterdam]

Eva Gonggrijp (NL) ON ENTRE, 2018

Multidisciplinary installation,

Sloterkade 171, Amsterdam

‘Once I dreamt that I walked through my old dollhouse, empty but full of atmosphere, waking up with a story, of which the words got lost’

Eva Gonggrijp

Memories want to be explored and recalled from the merciless passing by and disappearing, which is the essence of time. Memories do not agree with the one-way traffic of the time of the clock. They cling to other memories; if they venture back into times past, it is to move forward. Objects play a vital part in this. When you inherit precious objects, you do not inherit just the material, but also traces of people, memories of them and of particular situations, sometimes going back generations. There is nothing more lonely than a ring slipping off a finger with its destination unknown.

Gonggrijp’s grandmother built a dollhouse for her, the Eva Hof [Eva’s court], an almost perfect replica of her own house. A great part of her hidden past, her losses and dreams were echoed in the dollhouse. For Eva in turn, her grandmother’s house and the dollhouse in it became a safe haven, something to hold on to during a turbulent youth.

The technique of virtual reality enables Gonggrijp to wander around in her dream and share it with others. They are almost inaudible stories which dart out from the cracks of times past, from the space between things, from the silence in between the sounds. Who enters this space changes from subject to participating and direct object, since the traces of the past are not yours but do need your sensory perceptions to come to life.

Eva Gonggrijp [NL, 1960] – Lives and works in Amsterdam – KABK [Den Haag]. Exhibitions: Vleeshal [Haarlem], Gemeente Museum [Den Haag], Vishal [Haarlem], Arti et Amicitae [Amsterdam], Mediamatic [Amsterdam]

Eva Gonggrijp (NL) ON ENTRE, 2018

Multidisciplinary installation,

Sloterkade 171, Amsterdam

‘Once I dreamt that I walked through my old dollhouse, empty but full of atmosphere, waking up with a story, of which the words got lost’

Eva Gonggrijp

Memories want to be explored and recalled from the merciless passing by and disappearing, which is the essence of time. Memories do not agree with the one-way traffic of the time of the clock. They cling to other memories; if they venture back into times past, it is to move forward. Objects play a vital part in this. When you inherit precious objects, you do not inherit just the material, but also traces of people, memories of them and of particular situations, sometimes going back generations. There is nothing more lonely than a ring slipping off a finger with its destination unknown.

Gonggrijp’s grandmother built a dollhouse for her, the Eva Hof [Eva’s court], an almost perfect replica of her own house. A great part of her hidden past, her losses and dreams were echoed in the dollhouse. For Eva in turn, her grandmother’s house and the dollhouse in it became a safe haven, something to hold on to during a turbulent youth.

The technique of virtual reality enables Gonggrijp to wander around in her dream and share it with others. They are almost inaudible stories which dart out from the cracks of times past, from the space between things, from the silence in between the sounds. Who enters this space changes from subject to participating and direct object, since the traces of the past are not yours but do need your sensory perceptions to come to life.

Eva Gonggrijp [NL, 1960] – Lives and works in Amsterdam – KABK [Den Haag]. Exhibitions: Vleeshal [Haarlem], Gemeente Museum [Den Haag], Vishal [Haarlem], Arti et Amicitae [Amsterdam], Mediamatic [Amsterdam]

Eva Gonggrijp (NL) ON ENTRE, 2018

Multidisciplinary installation,

Sloterkade 171, Amsterdam

‘Once I dreamt that I walked through my old dollhouse, empty but full of atmosphere, waking up with a story, of which the words got lost’

Eva Gonggrijp

Memories want to be explored and recalled from the merciless passing by and disappearing, which is the essence of time. Memories do not agree with the one-way traffic of the time of the clock. They cling to other memories; if they venture back into times past, it is to move forward. Objects play a vital part in this. When you inherit precious objects, you do not inherit just the material, but also traces of people, memories of them and of particular situations, sometimes going back generations. There is nothing more lonely than a ring slipping off a finger with its destination unknown.

Gonggrijp’s grandmother built a dollhouse for her, the Eva Hof [Eva’s court], an almost perfect replica of her own house. A great part of her hidden past, her losses and dreams were echoed in the dollhouse. For Eva in turn, her grandmother’s house and the dollhouse in it became a safe haven, something to hold on to during a turbulent youth.

The technique of virtual reality enables Gonggrijp to wander around in her dream and share it with others. They are almost inaudible stories which dart out from the cracks of times past, from the space between things, from the silence in between the sounds. Who enters this space changes from subject to participating and direct object, since the traces of the past are not yours but do need your sensory perceptions to come to life.

Eva Gonggrijp [NL, 1960] – Lives and works in Amsterdam – KABK [Den Haag]. Exhibitions: Vleeshal [Haarlem], Gemeente Museum [Den Haag], Vishal [Haarlem], Arti et Amicitae [Amsterdam], Mediamatic [Amsterdam]

Hertog Nadler (NL/IL) DOUBLE TAKE, 2018

Site-specific installation,

Hoofddorpplein, Amsterdam

In their work, Hertog Nadler rely on a variety of strategies in order to propose an alternative outlook toward the phenomenon of time. Combining photography,

film, performance and installation enables the artist duo to blend historical periods, freeze a moment in time/space or highlight multiple aspects of a situation simultaneously.